Fire behavior in humanitarian dwellings is vastly different than in a building fire. Fanned by ample fuel sources and airflow, the intensity and speed with which fires in refugee camps spread are more akin to a wildland fire, explains Maryland Engineering Professor Arnaud Trouvé, the 2017 recipient of the International FORUM of Fire Research Directors’ Sjölin Award and co-chair of the U21 International Fire Safety Consortium. Human behavior is also a factor; most people misinterpret the speed of fire, says Trouvé, which can travel faster than a human can run.

In 2022, Milke and then UMD graduate student Genevieve Tan (’21, M.S. ’22) joined researchers from Stellenbosch and MOAS’ Richard Walls and Paul Chamberlain to look more closely at Kutupalong Balukhali and piece together what took place—from the path of fire to response and evacuation—during those seven hours in March 2021. Investigations after fires in refugee camps are often stymied by a lack of resources, but also a lack of evidence, says Antonellis.

“When these big fires occur, we never really find out from a scientific perspective why something happened the way it did,” she said. “There is a need for academia to develop methods for data collection and reporting, and use that information to characterize and understand the problem.” Milke, Tan, and their fellow researchers relied heavily on conversations with first responders and refugees on What’s App, on-the-ground accounts, information from international organizations, and media coverage. Theirs was the first detailed documentation of a large-scale refugee camp incident in academic literature.

“When these big fires occur, we never really find out from a scientific perspective why something happened the way it did,” she said. “There is a need for academia to develop methods for data collection and reporting, and use that information to characterize and understand the problem.” Milke, Tan, and their fellow researchers relied heavily on conversations with first responders and refugees on What’s App, on-the-ground accounts, information from international organizations, and media coverage. Theirs was the first detailed documentation of a large-scale refugee camp incident in academic literature.

The vulnerability of these camps and their residents to fire “is not talked about; to a great extent, these are forgotten people,” said Milke. “There is concern and care being taken through many international relief organizations, but it’s not something that gets as much attention in the United States.”

That might be in part because of how fire is experienced in the U.S., Antonellis says. While the country does experience social and economic inequities when it comes to fire, emergency response is often established and robust, insurance is widely available, and surrounding communities frequently respond with an outpouring of support. For already vulnerable refugees, she says, fire, the profound loss of livelihood and access to schools and healthcare, and the erasure of property including cash and identification papers are a re-traumatization.

While engineering plays an important role in understanding the issue, Antonellis points out, it is just one piece of a complex puzzle that cannot be solved without also considering the economics, social dimensions, and politics at play. The humanitarian system, a mechanism set into motion by disaster or conflict, must make quick decisions about the construction and management of camps as refugees pour into them in real-time.

“Fire risk is emerging as the camp is created,” Antonellis said. “It’s easy to say, ‘why don’t you space the tents further apart or ban candles?’ From a technical perspective it feels like a straightforward problem to solve, but it’s not a technical problem: It’s a sociotechnical problem.”

The human element of fire is what ultimately drew Tan to fire protection engineering, she says. At Maryland she found opportunity to study disaster resilience through an internship with the National Institute of Standards and Technology, which offered her an eye-opening view of the struggles people face in informal settlements.

As Tan began her graduate degree, the timing of Milke’s work with Kindling couldn’t have been better. Under Milke and Trouvé’s guidance and supported by a John L. Bryan Graduate Research Assistantship, Tan developed a thesis project to quantify the fire risk and burn behavior of humanitarian shelters using a YouTube video of a shelter fire conducted by UNHCR’s Site Management Engineering Project. Using MATLAB-based image processing, Tan compared the video with an identical dwelling created using Fire Dynamics Simulator, a modeling software that until now has only been used to model room or building fires. She was able to successfully reconcile characteristics including flame height, temperature, intensity, heat release, and spread—critical steps for understanding the unique characteristics of shelter fires.

In the future, Tan’s model could be configured to different dimensions, material properties, and contents (such as furniture) as more and better data become available. Simulations based on her model could help understand the risk of spread and may inform the spacing of dwellings. Now graduated from Maryland Engineering and working in fire safety consulting and system design for Baltimore-based Jensen Hughes, Tan hopes her work provides a foundation for another student to pick up where she left off.

“The one thing I learned through this process is that any conclusions I’ve made in my research aren’t conclusive,” she said. “I had such a limited scope of data to work with, and the nature of the problem makes things very hard to nail down right now. But it’s so important for people to continue working in this space.”

Learn about Tan's research on Instagram

As research on fire risk in humanitarian settlements continues—at Maryland, and at just a handful of other universities around the world studying the problem—so do the fires. On January 18, 2023, a camp of 3,000 refugees on the border of Bangladesh and Myanmar was set ablaze by militant groups, displacing hundreds; on March 5, 2023, yet another massive fire ripped through Rohingya refugee camps in southeastern Bangladesh, displacing an additional 12,000.

According to Deb Niemeier, the Clark Distinguished Chair of Energy and Sustainability at Maryland Engineering and winner of the Franklin Institute’s 2023 Bower Award and Prize for Achievement in Science, it’s only been within the last decade that engineers have embedded into the logistics of global humanitarian challenges such as the refugee crisis—but it’s an area where engineers can make significant impact. Research can help bridge the significant firsthand knowledge from organizations like UNHCR with the practice and models to understand how solutions could work on the ground.

According to Deb Niemeier, the Clark Distinguished Chair of Energy and Sustainability at Maryland Engineering and winner of the Franklin Institute’s 2023 Bower Award and Prize for Achievement in Science, it’s only been within the last decade that engineers have embedded into the logistics of global humanitarian challenges such as the refugee crisis—but it’s an area where engineers can make significant impact. Research can help bridge the significant firsthand knowledge from organizations like UNHCR with the practice and models to understand how solutions could work on the ground.

“Engineers are terrific at figuring out logistical concerns,” Niemeier said, “so the role for engineers is huge. We can work on very specific issues like fire risk, and raise a vigilant, observant practice so that it’s safer.”

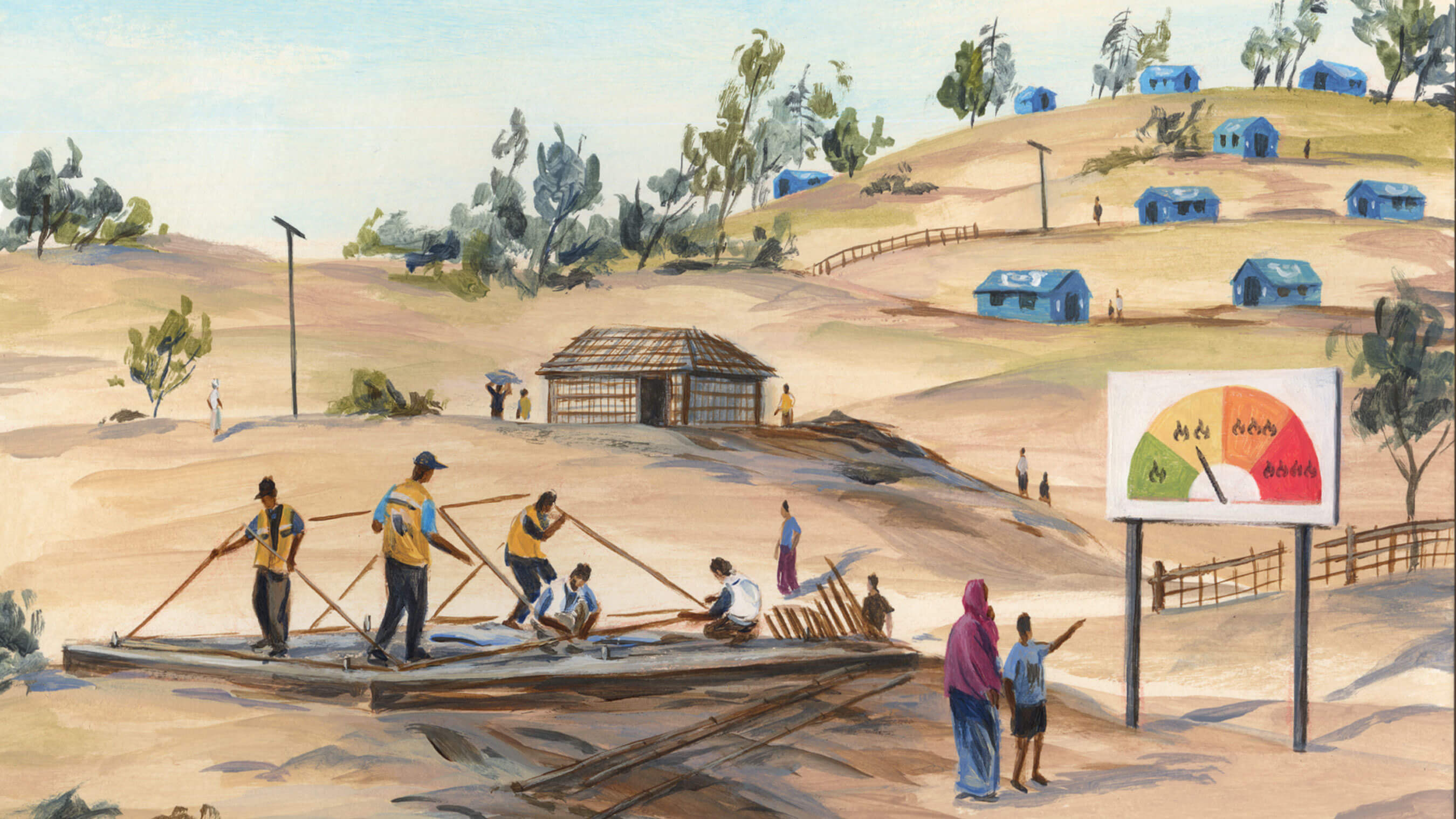

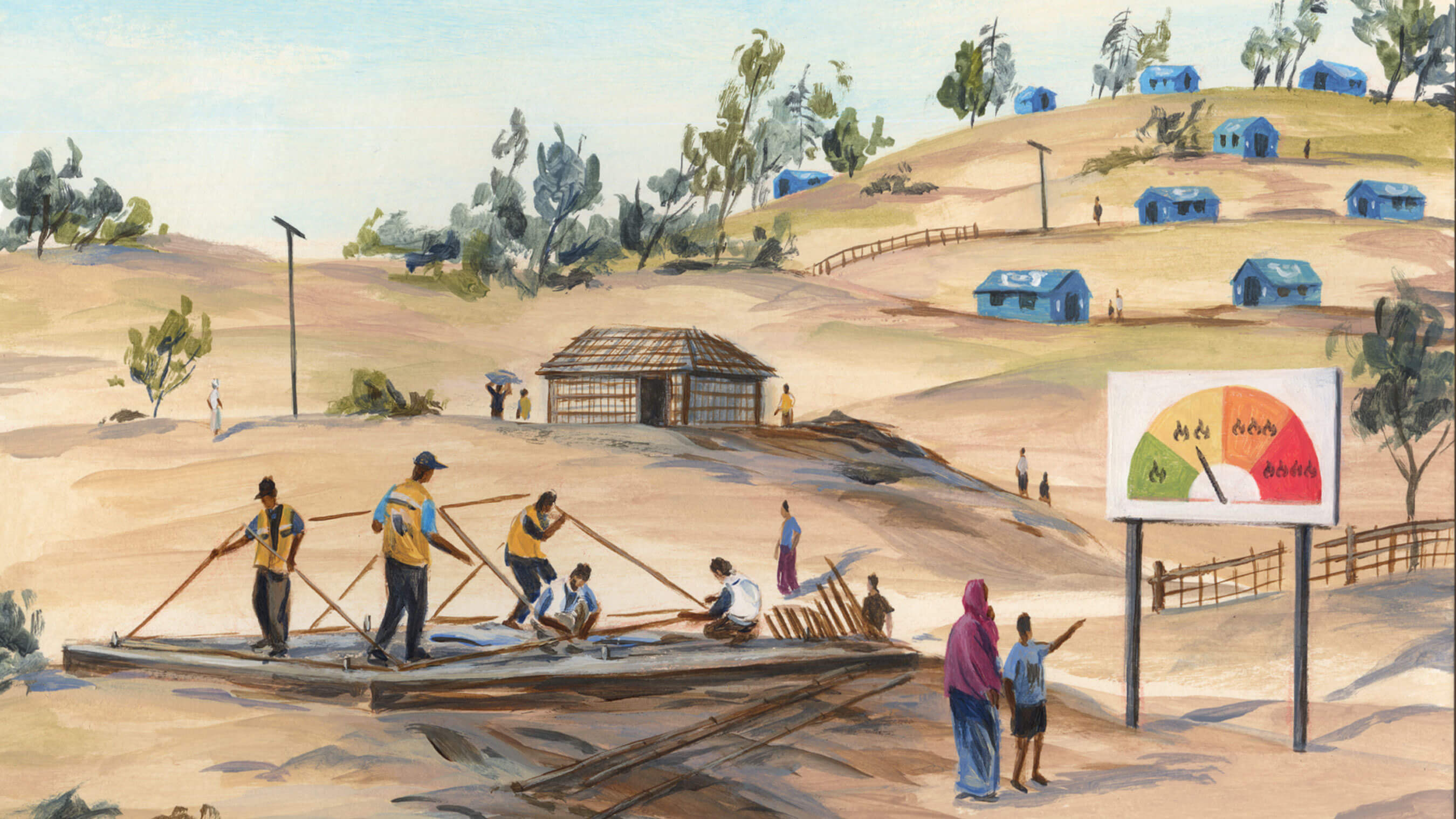

Ongoing collaboration and idea exchange with the academic community, says Graham, is essential for creating not just global awareness, but also a global response. He says that research, like the kind undertaken by Milke and students at Maryland, will keep the issue raised—as well as provide the foundation, best practices, and knowledge to establish fire management standards for refugee camps. Those standards, says Milke, could include a hazard warning system, similar to those used in high-risk wildfire areas, based on environmental conditions and density of the camps to alert refugees to take care with open flames and cooking.

“‘Red flag days’ have proven very effective for raising awareness in other parts of the world,” Milke said. “Could we accomplish the same here?”

One thing that researchers, first responders, and students all agree on: fire risk in refugee camps isn’t a problem that engineers can solve alone; it will take working with social scientists, economists, policy experts, and others to understand the issue’s complicated context.

That collaboration will help unpack the many questions still unanswered—and lead to real innovation, says Antonellis, who notes that Maryland’s strength as a hands-on, interdisciplinary-focused university makes it uniquely poised to drive the conversation.

“This is where academia can make the biggest difference,” she said. “We need research, like what’s happening at Maryland, to push under the noses of practitioners and stakeholders to provide them with the information they need to make better decisions.

“It’s transformative for our work.”

This story first appeared in the spring 2023 issue of Engineering at Maryland magazine. Story by Maggie Haslam; illustrations by Sally Deng.

In total, the fire burned for seven hours, scorched over 160 acres, killed 15 people, and displaced another 45,000. According to emergency responders on the scene, the magnitude of the fire, lack of water, and narrow roads hampered their efforts; the fire was only controlled once there was nothing left to burn.

In total, the fire burned for seven hours, scorched over 160 acres, killed 15 people, and displaced another 45,000. According to emergency responders on the scene, the magnitude of the fire, lack of water, and narrow roads hampered their efforts; the fire was only controlled once there was nothing left to burn.  Milke recruited a legion of young people—from Maryland high school students to Terps at the undergraduate and graduate levels—to gather and organize data and confer with faculty at Stellenbosch, experts at Kindling, and frontline responders at organizations like MOAS. Students conducted initial investigations of fire phenomena in informal settlements in South Africa and preliminary modeling and simulations of evacuations using Pathfinder software and Google Earth imagery. A challenge with informal settlements, however, is the hands-off approach of local governments: there is no overseeing body to collaborate with on possible interventions or solutions. Further conversations with colleagues at Stellenbosch suggested a shift to refugee camps.

Milke recruited a legion of young people—from Maryland high school students to Terps at the undergraduate and graduate levels—to gather and organize data and confer with faculty at Stellenbosch, experts at Kindling, and frontline responders at organizations like MOAS. Students conducted initial investigations of fire phenomena in informal settlements in South Africa and preliminary modeling and simulations of evacuations using Pathfinder software and Google Earth imagery. A challenge with informal settlements, however, is the hands-off approach of local governments: there is no overseeing body to collaborate with on possible interventions or solutions. Further conversations with colleagues at Stellenbosch suggested a shift to refugee camps.  “When these big fires occur, we never really find out from a scientific perspective why something happened the way it did,” she said. “There is a need for academia to develop methods for data collection and reporting, and use that information to characterize and understand the problem.” Milke, Tan, and their fellow researchers relied heavily on conversations with first responders and refugees on What’s App, on-the-ground accounts, information from international organizations, and media coverage. Theirs was the first detailed documentation of a large-scale refugee camp incident in academic literature.

“When these big fires occur, we never really find out from a scientific perspective why something happened the way it did,” she said. “There is a need for academia to develop methods for data collection and reporting, and use that information to characterize and understand the problem.” Milke, Tan, and their fellow researchers relied heavily on conversations with first responders and refugees on What’s App, on-the-ground accounts, information from international organizations, and media coverage. Theirs was the first detailed documentation of a large-scale refugee camp incident in academic literature. According to

According to