News Story

UMD, MIT team for new 'superhydrophobic surfaces' patent

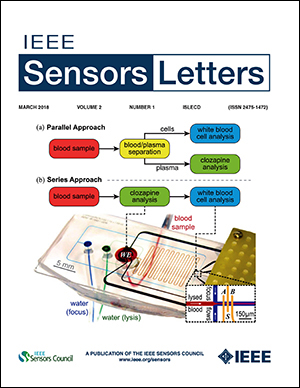

A team composed of researchers with ties to the University of Maryland and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology was awarded U.S. Patent 8,986,814 on March 24, 2015 for “Superhydrophobic surfaces.”The patent is for a new kind of surface that mimics the water-resisting properties of wetland plant leaves. The new surfaces have a hierarchical structure with both microscale and nanoscale features. They can be fabricated using biological virus nanostructures as self-assembled templates. The “superhydrophobic” properties of these surfaces could one day make them useful as coatings on buildings, solar cells, and textiles. They also could be employed in applications that require drag reduction and increased heat transfer.

The research team includes MIT Associate Professor of Mechanical Engineering Evelyn Wang; ISR Director Reza Ghodssi (ECE/ISR); Professor James Culver (Plant Science & Landscape Architecture); Drexel University Assistant Professor of Mechanical Engineering and Mechanics Matthew McCarthy; Ryan Enright of Bell Labs Ireland, a former postdoctoral researcher at MIT; and ISR postdoctoral researcher Konstantinos Gerasopoulos (EE Ph.D. 2012).

McCarthy is a former ISR postdoc who worked with Dr. Ghodssi; Gerasopoulos currently works with Dr. Ghodssi and is his former student.

About the patent

Superhydrophobic surfaces, with static contact angles greater than 150.degree., droplet hystereses less than 10.degree., and roll-off tilt angles typically less than 2.degree., resist wetting and exhibit self-cleaning properties.

In nature, a wide array of wetland and aquatic plant leaves are superhydrophobic and self-cleaning. Due to the abundance of water, these wetland plants do not rely on taking in moisture through their leaves to hydrate, and resist wetting when it is raining.

These properties actually are a necessity for the plants’ survival. Shedding water from the surface dramatically increases their uptake of carbon dioxide for photosynthesis. In addition, their self-cleaning abilities reduce the formation of bacteria and fungi that would otherwise thrive in the hot, moist wetland climate.

Scientists have focused significant efforts on mimicking the naturally occurring structures of the leaves of one of these plants, the lotus. However, existing fabrication methods limited scientists' ability to accurately mimic both the surface structures and resulting water-repellent behavior of the lotus.

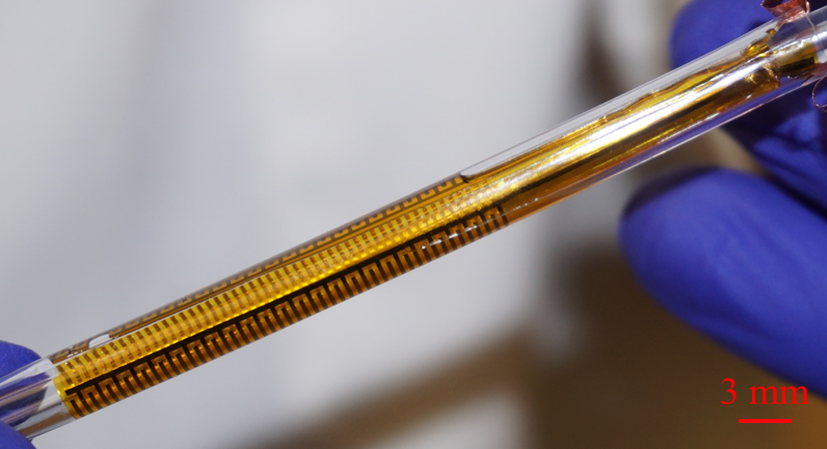

To overcome this limitation, the UMD-MIT research team used a genetically engineered mutation of the tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) as their fabrication template. TMV, like other viruses, is a self-assembled biological nanostructure. Genetic engineering can change the TMV to give it properties useful in fabrication, such as an affinity for a surface. The virus then can serve as a nanoscale template. When used in this way, the virus becomes inert. In this case, the research team was able to use the TMV template to successfully build a hierarchically structured, superhydrophobic surface that also has condensation mass and heat-transfer properties.

Members of the research team have experience using TMV as a template in previous work; for example to build a new generation of small, powerful and highly efficient batteries and fuel cells.

Published March 26, 2015