News Story

UMD Researchers Help Measure DART’s Success

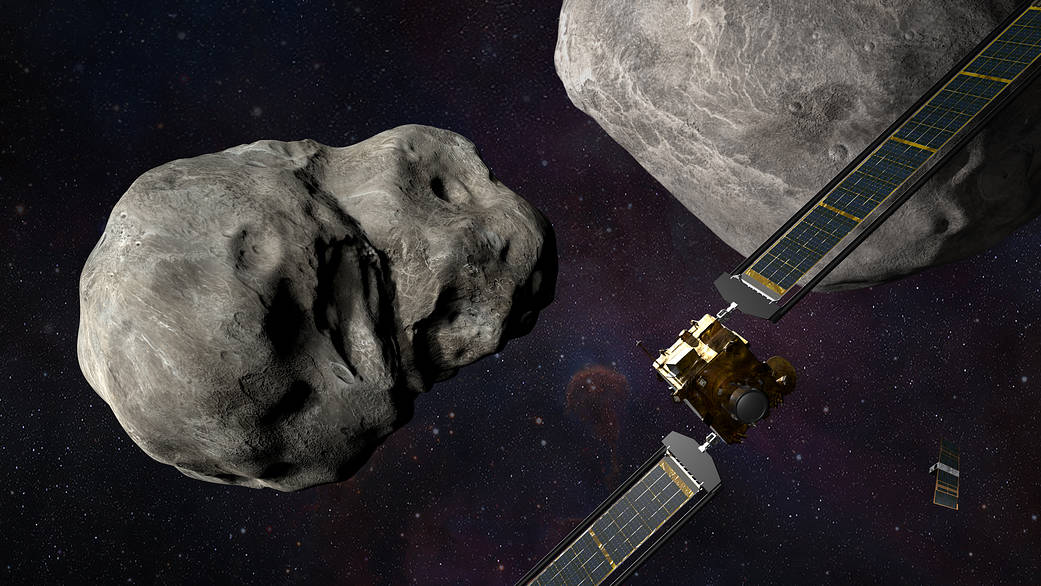

Last September, NASA intentionally crashed a probe into the surface of a moon orbiting the asteroid Didymos in order to help ascertain whether similar procedures could be used to deflect space objects on a collision course with Earth.

Last September, NASA intentionally crashed a probe into the surface of a moon orbiting the asteroid Didymos in order to help ascertain whether similar procedures could be used to deflect space objects on a collision course with Earth.

Scientists, including UMD aerospace engineering postdoctoral researcher Yun Zhang and colleagues at the UMD astronomy department, have since been parsing data gleaned from the mission. Their findings have now been published in a series of five papers appearing in Nature.

A key takeaway is that the idea worked. As Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) planetary scientist R. Terik Daly and his co-authors demonstrate in their paper, the moon Dimorphos’s orbit changed as a result of being struck by the DART probe. Another paper, with APL scientist Andrew F. Cheng as the lead author, details the momentum transfer that occurred as the probe smashed into the moon’s surface.

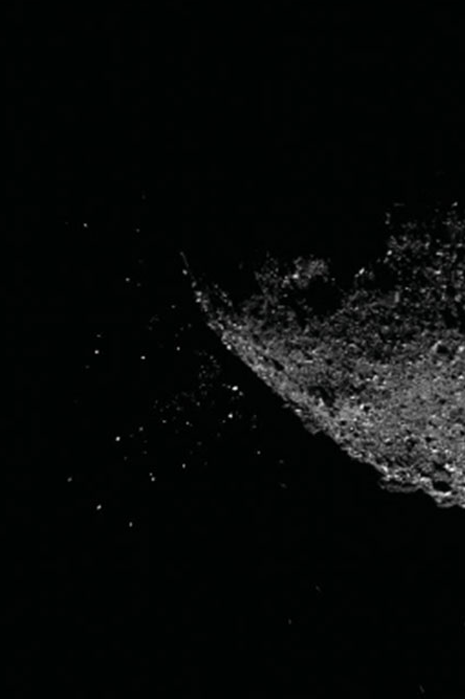

Analysis of the DART data “demonstrates that kinetic impact is a viable technique to deflect an asteroid,” said UMD’s Zhang, a contributor to both papers. “DART impacted Dimorphos at a site within 25m of its geometric center. The momentum transferred to Dimorphos from DART is estimated to be more than twice DART’s momentum, due to the recoil force from impact ejecta. This suggests that the DART kinetic impact was highly effective in modifying Dimorphos’s orbit around Didymos."

Based at UMD’s Planetary Surfaces and Spacecraft Lab, which is led by Professor Christine Hartzell, Zhang has previously been involved in modeling the asteroid Bennu. Her specific role in the Nature studies was to interpret the density of the target based on her previous work on asteroids, thus enabling the team to obtain a more accurate estimate of the momentum transfer from the probe as it impacted the moon. Drawing from her Bennu research, she also provided insights concerning the moon’s geophysical features. “Observations during and following the DART impact provide important information on the geological features of this binary system and the dust dynamical evolution in such an environment. In my further studies, I want to understand how this binary system formed in the first place,” she said.

Besides demonstrating the feasibility of knocking space objects off a collision course with Earth, DART was important in another way: the information gained from the mission can be used to calibrate and validate numerical models and simulations that scientists in the future can use before a deflection mission is launched.

“With an improved understanding of an asteroid’s structural response to impact, before undertaking any physical maneuver to deflect an asteroid, the scientists can run simulations first to predict the outcome and assess the deflection efficiency,” she explained.

The need for effective methods of asteroid avoidance has been an ongoing topic of concern for the space community, and increasingly for lawmakers as well. In 2005, the U.S. Congress passed legislation directing NASA to carry out a comprehensive survey of near-earth space objects and devise methods for deflecting them. An asteroid collision is thought to have triggered the extinction of all non-avian dinosaurs, and even a smaller-scale collision in the future could wreak havoc on the Earth’s biosphere.

Space researchers, including authors of the Nature papers, stress that collision scenarios remain highly unlikely in the near future. In February, the European Space Agency detected an asteroid measuring around 50 m that could hit Earth in 2046, but the likelihood is considered slim.

Published March 27, 2023