News Story

Monitoring Wastewater for COVID-19

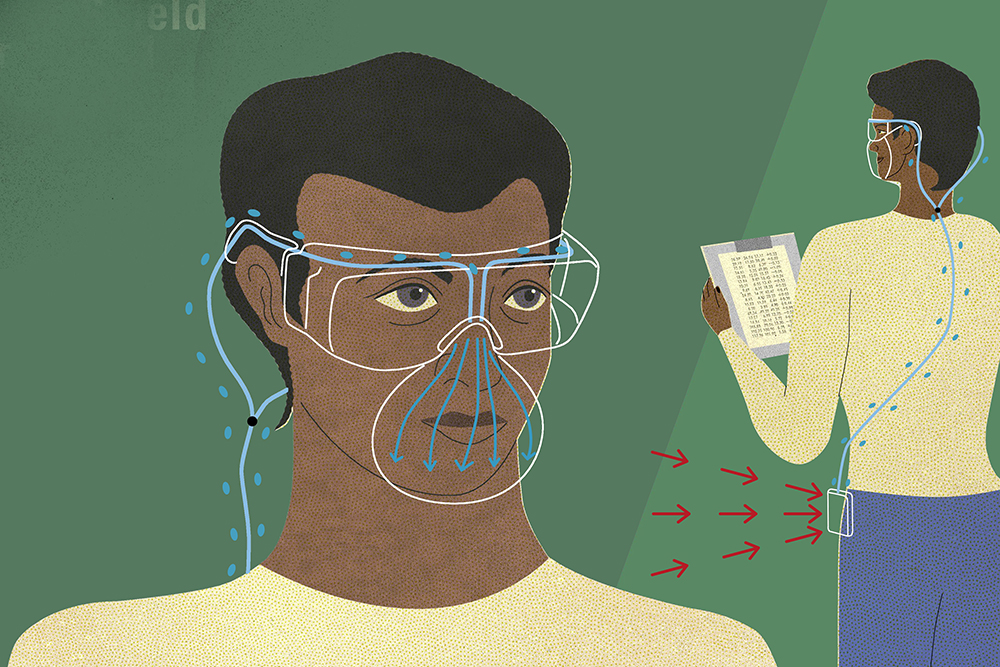

The earliest indicator of COVID-19 may not be what—or where—one expects. Roughly five days before an infected person begins showing symptoms, their body actively sheds the virus when they use the bathroom, sending microbial clues into the sewer system. It’s within those networks of wastewater pipes, Birthe Kjellerup believes, that researchers may find the key to curbing future outbreaks.

“Certain genes can be detected in wastewater,” says Kjellerup, Pedro E. Wasmer Professor of civil and environmental engineering, who has studied microbial communities called biofilms for more than 25 years, “so in fact, monitoring wastewater systems could be an excellent surveillance method for viruses like COVID-19. Experts don’t believe it’s live infection, but by tracking how much of the virus is in the water, we can be alerted of a brewing outbreak before individuals even show symptoms.”

Working with the Washington Suburban Sanitary Commission, Kjellerup and postdoctoral researcher Devrim Kaya placed automatic collection devices in six locations around Montgomery and Prince George’s counties, two of Maryland’s hardest-hit counties by COVID-19.

Extracted twice weekly, the researchers can determine if viral loads are increasing, decreasing, or flat from sample to sample. Early analysis found evidence that coincided with infection trends seen around the counties throughout the summer, such as a general decline in numbers throughout June and July. Because the organisms serve as early detection, Kjellerup says they can clue agencies in on possible spikes; by adding more sensors throughout the county, municipalities can gain detailed, neighborhood-specific data and even isolate building-specific outbreaks, such as at a nursing home or school.

Kjellerup and colleagues Clark Distinguished Chair and Maryland Transportation Institute Co-director Deb Niemeier and University of Maryland School of Medicine Professor Soren Bentzen are seeking new funding to analyze samples and overlay them with trip and census data and other socioeconomic variables to create a model that offers a more comprehensive look at the pandemic trajectory and impact, particularly for different communities and demographics. This tool, says Kjellerup, could potentially help government agencies make more informed, surgical decisions about what can remain open and what needs to close.

“With work like this we wouldn’t necessarily have to shut the entire state down,” she says. “Western Maryland, for instance, where the models have been better, might be able to open more widely.”

This fall, Kjellerup’s work is also helping UMD with early detection on campus. As part of an initiative spearheaded by the Office of the Provost and in conjunction with the School of Public Health and Facilities Management, strategic sampling is taking place near high concentrations of students—wastewater pipes coming from dorms, for instance—to help monitor presence of COVID-19 and determine when and where to ramp up testing and tracing.

Published August 31, 2020