News Story

How COVID Complicates a Historic Hurricane Season

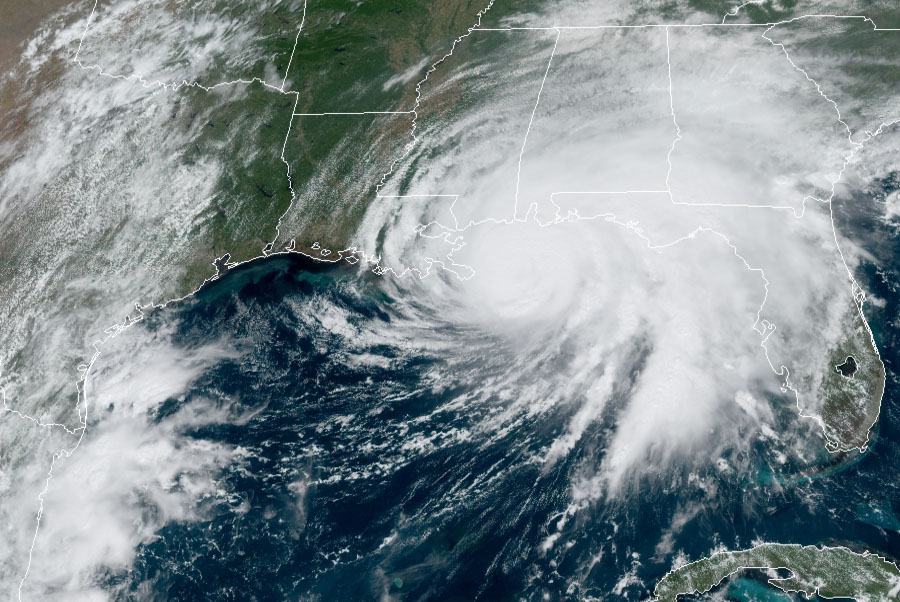

Emergency response experts have studied events like Hurricane Sally, forecast to make landfall today along the Gulf Coast, for decades. They’ve also planned for giant wildfires like those burning on the West Coast, while public health scientists pondered hypothetical pandemics similar to COVID-19.

No one ever rolled the most active hurricane season ever, a wave of apocalyptic fires and a global pestilence all into a single nightmarish scenario—until reality did, said Sandra Knight, a senior research engineer in the University of Maryland's Center for Disaster Resilience (CDR) and a consultant who has held senior positions at the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the Federal Emergency Management Agency. CDR is based at the department of civil and environmental engineering, part of UMD's A. James Clark School of Engineering.

As climate change, rising global population and other factors make such cascading events more likely, disaster response planners need to raise the complexity of their thinking as they prepare for worst-case scenarios, she said.

As climate change, rising global population and other factors make such cascading events more likely, disaster response planners need to raise the complexity of their thinking as they prepare for worst-case scenarios, she said.

“You have to imagine the impossible—the worst-case scenario and how you would deal with it,” she told Maryland Today in an interview. “I think we’re going to have to start imagining pretty hard to come up with something worse than this,” she said.

How is the response to Hurricane Sally muddled by the coronavirus pandemic?

This is true of this hurricane as well as the fires out West: When you have to evacuate people, you have to evacuate them somewhere, and many people, particularly people of lower means or without transportation, end up in evacuation shelters. But now the people in charge of them have to think how many people they can get in one shelter, how do you space them to keep them safe? Do you have COVID PPE available, masks to pass out to people? You have all these things happening at once but the same number of emergency responders.

To turn the question around, how does a fire or flood complicate dealing with the pandemic?

If people have experienced smoke inhalation, it can complicate their lung issues from COVID. There’s also the capacity issue in hospitals and emergency rooms. By crowding people together in these emergency situations, it increases the possibility COVID could spread. It requires you to balance your risks—if it comes down to me having to choose between running from the fire or socially distancing, I’m running from the fire. But that balancing act means I am more likely to get COVID.

"As you go through the alphabet with storm names, this is the earliest we’ve ever gotten this high. Sally is barreling in, and there are several other storms out in the Atlantic that we don’t know where they’re going or what they’re going to do. And hurricane season doesn’t end until November."

Dr. Sandra Knight, Senior Research Engineer, UMD Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering

How bad is this hurricane season?

As you go through the alphabet with storm names, this is the earliest we’ve ever gotten this high. Sally is barreling in, and there are several other storms out in the Atlantic that we don’t know where they’re going or what they’re going to do. And hurricane season doesn’t end until November.

Why are we seeing so much hurricane activity?

Climate change—there's no denying that. We’ve known for decades it would be impacting natural disasters, and it wasn’t always a partisan issue. We listened to the science decades ago, and now we've moved into either having our heads in the sand, or deciding this is an issue of one party or the other. Even if we stop carbon emissions tomorrow, we're going to have decades of bad storms and increased hazards as a result of climate change.

How should we, as a society, respond to this maelstrom of disasters?

We're going to have to think about these compound events and how complex they are. I think we're going to have to be serious about our response to climate change, and we're going to have to quit using fossil fuels, be kind to our national resources and take care of our planet. I think we've all got an individual responsibility to be as prepared as we can, and a responsibility to believe the science.

How do you convince society to believe the science?

I've worked with a lot of scientists and engineers, and we all feel like we're apolitical and that our job is to bring forth the truth in our facts and our figures. But now it's time for us to have more of a voice, and it's a time for us to speak truth to power. It's time for us to be the communicators of good science, and not sit behind the wall thinking somebody else is going do it.

This article first appeared in Maryland Today. Photo credit: NOAA.

Published September 15, 2020